The ESP32-C3 has no business running a NES emulator. It's a single-core RISC-V chip clocked at 160 MHz with 400 KB of RAM. No dedicated graphics hardware, no co-processor, nothing. Just a CPU and some peripherals.

I got Super Mario Bros running on it averaging at around 33 frames per second, and hit as high as 37 frames! Here's the whole story.

The Porting Process

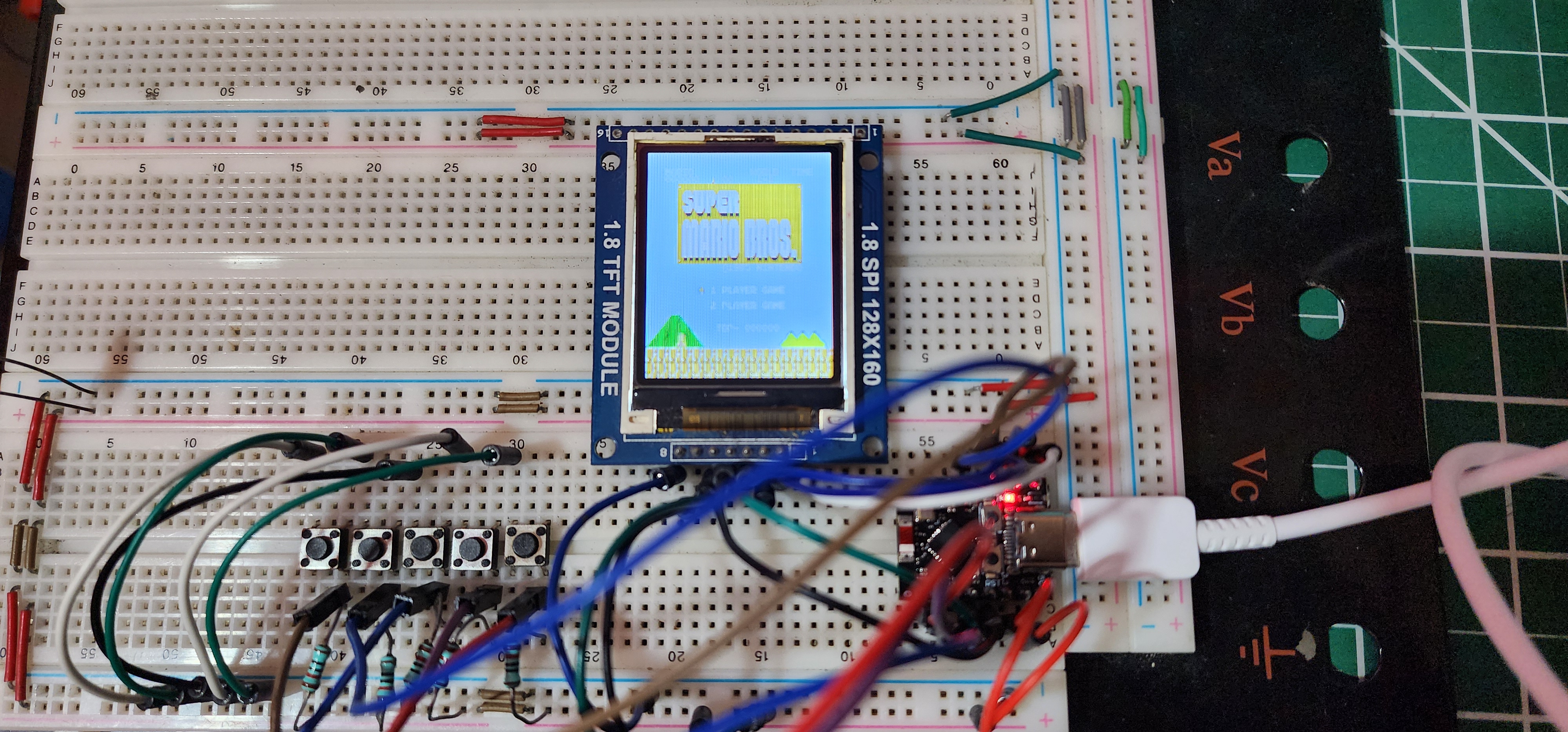

The hardware is about as minimal as it gets. An ESP32-C3 Super Mini board, an ST7735 128x160 SPI display, and five buttons wired to GPIO pins. A, B, START, LEFT, RIGHT. That's it. Total cost for the whole thing is maybe $5 if you're buying off AliExpress. The chip itself runs about a dollar at volume.

For the emulator core I started digging around repos and looking at tutorials, I saw a lot of promise but none of them met my fancy. My goal was no audio, which is fine because I just wanted to see how I could get this thing running and adding audio overhead even with I2S for me was not in the origial design, based on my research and what Claude and ChatGPT told me I'd be lucky to get 8-10 FPS from any emulator if it runs at all as the ESP32-C3 dosen't have the memory or processing power and it suggested a bunch of other ESP32 and STM32 chips. Nofredo was touted as the best and only one worth looking into, and digging around that seemed plausible, but I didn't listen though, I wanted it on a $1 RISC-V ESP32 MCU. Word to the wise if it can be done, do it regardless of what the LLM says. The important thing for me was that it had to run on a microcontroller without wanting to throw the board out the window.

Step one was getting the ST7735 up and running, it was hard to find a good library for ESP32C3 with ST7735, they all seem to use Arduino IDE and I prefer ESP-IDF and the command line. So I ported a PIC32 library I had from about 9 or so years ago:

The next step was to get the display running and using DMA to reduce overhead on the CPU. Standard stuff, I've used the ST7735 so much that I could write a driver for it in my sleep by now, and ESP-IDF is rather straightforward to use.

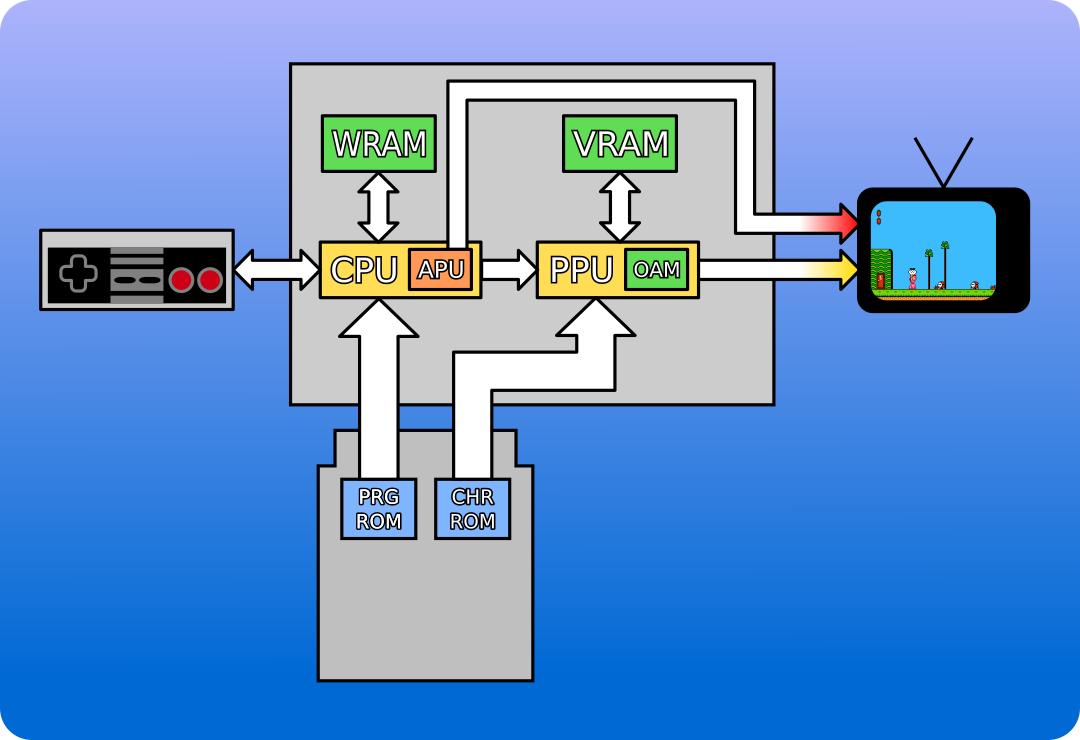

Once I started writing the emulator, the frist thing I ran into was memory issues. All the emulators I looked at allocated a full 256x240 framebuffer using 32-bit pixels. That's 245 KB just for the screen buffer. The ESP32-C3 has 400 KB total. Once you account for FreeRTOS, the NES CPU and PPU state, and the ROM data, there's nothing left. Then the next step was to add the buttons. I knew from the start Super Mario Bros was my target so left, right, start ,select, A and B were the buttons I started with, and did a quick test to make sure the button can trigger actions on the screen.

So the framebuffer had to go. I replaced it with per-scanline rendering. Instead of drawing a full frame to memory and then pushing it to the display, the PPU renders one 256-pixel line, fires a callback, the callback scales it down to 128 pixels and streams it to the ST7735, and the PPU moves on to the next line. Total memory for the display path dropped from 245 KB to about 3 KB for line buffers. The other easy win was PRG ROM. The original code copies the ROM into a RAM array at startup. On a microcontroller you can just read it directly from flash using a const pointer. That freed up another 32 KB. Total memory usage went from 340 KB (wouldn't fit) down to about 63 KB (fits with room to spare).

So I slogged down an emulator, tried to leverage LLMs where I could, however they weren't that much help, and were more about distracting me telling me why X chip would be better than helping the cause.

After the port compiled and the display showed something recognizable, I measured the frame rate. 4.4 FPS. About 235 milliseconds per frame. Mario was basically a slideshow. But the game ran. The title screen worked, pressing START started the game, Mario moved when I pressed buttons. Everything was correct, just extremely slow. Time to start profiling.

Phase 1: PPU Memory Access (4 FPS to 10 FPS)

The biggest bottleneck was the PPU's memory access path. Every time the PPU needed to read a nametable byte or a palette entry, it went through a generic ppu_memory_access() function that checked address ranges, handled mirroring, and returned the byte. This function was getting called about 270,000 times per frame.

I replaced it with two small inline functions. ppu_read_nt() reads the nametable with mirroring logic baked in. ppu_read_pal() reads palette entries with the standard NES palette mirroring. Both resolve to a direct array index. No function call overhead, no address range checking at runtime. I also changed the PPU from stepping one pixel at a time to rendering a full scanline at once. Instead of 256 separate pixel operations per line, the PPU composites background tiles and sprites across the whole 256-pixel width in one go. Frame time dropped from 235ms to 90ms. FPS went from 4.4 to 10. Great that's about the limits the LLMs said I could reach, I tried again to optimzie with them but they broke more than fixed, so I knew it was time to go solo.

Phase 2: PPU Clock Batching (10 FPS to 14 FPS)

So I looked at my program, the main loop was calling nes_ppu_run() once for every single PPU clock cycle. That's 89,080 calls per frame. Each call did almost nothing except increment a counter and check if anything interesting happened at the current pixel position.

I wrote nes_ppu_run_clocks() which takes a clock count and jumps directly between event points. The only things that matter are pixel 0 of each visible scanline (render the line), pixel 257 of scanline 240 (post-render), pixel 1 of scanline 241 (set vblank, fire NMI), and pixel 1 of scanline 261 (clear flags). Everything between those points is just advancing the counters. This brought the call count from 89,080 down to about 700 per frame. The frame time dropped from 90ms to 60ms and FPS hit 14. I thought dang I was on fire how much further can I go!!!!

Phase 3: Per-Tile Rendering (14 FPS to 20 FPS)

My bottleneck was my PPU. The PPU was still iterating over 256 individual pixels per scanline for the background. But NES backgrounds are made of 8x8 tiles. Instead of looking up which tile a pixel belongs to 256 times, I switched to iterating over 33 tiles per scanline (32 visible plus one for fine scroll) and decoding 8 pixels at a time.

The tile decoding used a bit-interleave trick I picked up workong on embeeded displays over the years. NES tiles store two bitplanes separately, but you can merge them into a single 16-bit value with some shifting and masking, then extract all 8 two-bit color indices with shifts. It's the same approach Nofrendo uses. I also added palette caching. The attribute table lookup that determines which 4-color palette a tile uses was happening for every pixel. Now it happens once per tile and the result gets reused for all 8 pixels. That eliminated about 122,000 redundant attribute lookups per frame.

The other nice thing about per-tile rendering is that you can skip transparent tiles entirely. In Super Mario Bros, about 60% of the screen is sky, which uses tile index 0x24 with all-zero pattern data. When both bitplane bytes OR to zero, the tile is fully transparent and you just fill it with the backdrop color. No palette lookup, no compositing.

This got me to about 20 FPS with frame times around 40ms. So great I though, let me dig around and start seeing waht else is causign all the drama.

Phase 4: CPU Optimization (20 FPS to 20 FPS... sort of)

At this point the bottleneck had shifted. The PPU was no longer the problem. The 6502 CPU interpreter was eating about 70% of the frame time.

At this point I started digging around more and I looked at nofredo for inspiration, after all it was the closest thing I had,. I looked at how they ddi their CPU and I rewrote the CPU using the same techniques as Nofrendo. The accumulator, X, Y, program counter, and stack pointer get loaded into local C variables at the start of execution. I was like aha!! on RISC-V, the compiler can maps these directly to hardware registers. Bingo! The status register gets "scattered" into 6 separate flag variables (one for each flag), so testing the zero flag or negative flag is a single comparison instead of a mask-and-shift. All addressing modes and ALU operations are macros that inline everything!!!!

This eliminated about 50,000 pointer dereferences and 40,000 conditional branches per frame (my math may be off don't quote me on that). In theory. In practice the results were inconsistent. Some frames ran at 21ms, others spiked to 45ms. The RISC-V core only has 15 callee-saved registers and the scattered flags plus cached registers plus the loop variables were causing the compiler to spill to the stack on complex opcodes. I thought thats okay but I wasn't in the mood for hand crafted assembly.

I also introduced batch execution. Instead of returning to the main loop after every single 6502 instruction, the CPU runs a budget of cycles in a tight while loop. Scatter flags once at entry, combine once at exit. This cut function call overhead from 10,000 calls per frame down to about 262 (again don't quote me on this!!)

Average FPS was around 20, but with a lot of variance.

Phase 5: The Big PPU Rewrite (20 FPS to 33 FPS)

This is where things got interesting. I was looking and seeing my cycles gettigng gobbled up. Dang PPU I thought, so I went back to the PPU and looked at what was actually eating cycles. Three things stood out.

First, three arrays were being memset to zero every scanline. The sprite position array (256 bytes), the sprite color array (256 bytes), and the opaque tracking array (256 bytes). That's 768 bytes cleared 240 times per frame, which works out to about 180 KB of memsets per frame. For a chip with 400 KB of RAM total, that's a lot of memory bus traffic doing nothing useful.

I replaced the full-width sprite arrays with a compact sprite list. Instead of clearing a 256-byte array and then writing sprite pixels into it, the PPU scans OAM (Object Attribute Memory, I read an article on it and everything) and builds a small list of only the sprites that are actually visible on the current scanline. Each entry stores the X position, 8 decoded color values, the palette index, priority flags, and a sprite0 indicator. Scanlines with no sprites cost almost nothing.

Second, the PPU had three separate 256-pixel loops: one for sprite0 hit detection, one for sprite compositing, and one for background rendering. I merged them into a single pass. Render the background tile by tile directly into the output buffer, then composite sprites from the compact list in one shot.

Third, I eliminated an intermediate tile buffer and a memcpy. The old code rendered 33 tiles into a 272-pixel temporary buffer, then memcpy'd 256 pixels out of it (offset by the fine-x scroll value). The new code renders tiles directly into the output buffer, handling fine-x by skipping the first tile's leading pixels. That's 512 bytes of memcpy eliminated per scanline, which adds up to about 123 KB per frame.

I also added a palette dirty flag. The palette cache was being rebuilt every scanline (32 palette-to-RGB565 lookups, 240 times per frame) even though the palette almost never changes mid-frame. Now it only rebuilds when the game actually writes to palette RAM through the PPUDATA register. A bit hackt but it works.

The last piece was putting the hot functions in IRAM. This was another EURUKA monent. The ESP32-C3 normally runs code from flash through a cache. Cache misses on tight inner loops add up. Marking render_scanline(), render_sprites_scanline(), and nes_ppu_run_clocks() with IRAM_ATTR puts them in internal RAM where access is single-cycle. I also put nes_cpu_run() in IRAM since the CPU interpreter is the other hot path. That cost about 46 KB of IRAM but dropped EMU time by another couple milliseconds.

After all of this, frame time went from 45ms average down to 27ms. FPS jumped from 20 to 33. Rock solid, minimal variance.

The Display Path

The display side was less dramatic but still needed work. The NES renders at 256x240 and the ST7735 is 128x160, so I need to downscale both horizontally (2:1) and vertically (drop every 3rd scanline, turning 240 lines into 160).

For horizontal downscaling I initially just sampled every other pixel. This caused aliasing. The brick tiles in Super Mario Bros would flicker between their normal pattern and horizontal lines depending on the scroll position. Different scroll offsets moved which NES pixels landed on the even-numbered samples, and the regular brick pattern would alias differently each frame.

The fix was averaging adjacent pixel pairs instead of skipping. There's a fast way to average two RGB565 values: mask out the LSB of each color channel with 0xF7DE, shift each down by 1, and add. The LSB masking prevents bit bleeding between the color channels during the add. Maximum error is 1 LSB per channel, which is imperceptible.

For the SPI interface, I wrote a streaming API. ST7735_BeginFrame() acquires the SPI bus and sets a full-screen window command once. Then ST7735_PushPixels() streams pixel data in chunks without any per-chunk overhead. ST7735_EndFrame() releases the bus. The chip select and data/command pins use direct GPIO register writes instead of the ESP-IDF gpio_set_level() function, which is about 10x faster for pin toggling.

The SPI clock runs at 40 MHz. I tried 50 and 80 but the display time stayed at 6.9ms either way. The bottleneck is the ESP-IDF SPI driver overhead (transaction setup, mutexes), not the actual wire speed. The wire time for 40 KB at 40 MHz is only about 1ms.Dang ESP!

Fixing Small Mario

There was one bug that took a while to track down. In certain areas of the game, when Mario got hit and shrunk from big to small, he'd disappear completely. He'd come back when getting a star power-up or sometimes just randomly, but during normal walking he'd be invisible.

The original emulator was missing the sprite behind-background priority flag (don't ask). NES sprite attribute byte bit 5 controls whether a sprite renders in front of or behind the background. Without this check, the sprite composite was unconditionally drawing everything, and somehow the interaction between that and the rendering order was causing small Mario's sprites to get lost.

Adding the priority check was simple. Store the behind_bg flag per sprite in the compact sprite list, and during compositing only draw the sprite pixel if the flag is clear or the background at that position is transparent. One extra condition in the inner loop, zero performance cost, and Mario stopped disappearing. I also had to add proper 8x16 sprite support. The NES can run sprites in either 8x8 or 8x16 mode. The original code only handled 8x8. In 8x16 mode, the tile index byte works differently (bit 0 selects the pattern table, top tile is index AND 0xFE, bottom tile is index OR 0x01) and the row calculation needs to handle 16 rows instead of 8. Super Mario Bros uses 8x16 sprites for big Mario.

What's Next

There's no audio yet. The NES APU has 5 channels (2 pulse, 1 triangle, 1 noise, 1 DMC) and adding it would probably cost 3-5ms per frame, dropping things to about 27-28 FPS. Still playable. A MAX98357A I2S DAC would handle the output side for about $1.

The emulator only supports Mapper 0 games right now. That covers the original Super Mario Bros, Donkey Kong, Excitebike, and a handful of others. Adding Mapper 1 (MMC1) would open up Zelda, Metroid, and Mega Man 2. Mapper support is mainly a memory controller thing and wouldn't affect performance much, maybe I will add more mapper, but my ultimate RISC-V target is the CH32H417 series (which I'm patiently waiting on), so I want to do a full port to that Audio and all. The ESP32-P4 has dual cores at 400 MHz with a dedent pipeline. Either of those would hit 60 FPS without breaking a sweat. But there's something satisfying about squeezing 33 FPS out of a dollar chip.The code is built on ESP-IDF with the nes_emu core. If you want to try it yourself, you need an ESP32-C3 board, an ST7735 display, and some patience with the SPI wiring. The ROM gets embedded directly into the firmware binary using CMake's target_add_binary_data.

My biggest takeaway from this whole thing is that compiler optimization flags aren't magic. The ESP32-C3 was already running with -O2 and 160 MHz. The gains came from restructuring the code to do less work, not from hoping the compiler would figure it out.

Profile first, optimize the right thing, measure again. The boring advice turns out to be correct. Eliminating 180 KB of unnecessary memsets per frame sounds obvious in hindsight but it was invisible until I actually measured where the time was going.

Yea so that's it, I'll clean up the code and link to github at a later date...